Experimental physicists spend years producing analyses of LHC data, searching for deviations from the Standard Model or signs of “new physics”. Typically we are testing simplified models of new physics which are suggested by our theory colleagues. But what if a theorist comes up with a new model after the analysis is published, and wants to know what constraints exist on it from existing LHC measurements? Or worse, what if they only come up with their model 40 years from now, when the LHC is an ancient memory? We need to make sure that we’ve done a good job at analysis preservation, such that LHC results can be re-interpreted long in the future, the guarantee the long-term impact of our work!

Re-interpretation is often considered a branch of phenomenology. This is a topic which sits between theoretical physics (thinking up the new models which could extend the Standard Model) and experimental physics (building and exploiting our particle detectors, and analysing the data we collect with them). In brief, the role of phenomenology is to say “if you wanted to look for this model, what should you be searching for in your detector?” In other words, it’s the study of how new phenomena (thus the name) would manifest in an experiment. Re-interpretation is part of that process: we take new physics models and check if they would already be covered by existing experimental efforts.

Analysis Preservation

“Analysis Preservation” is the process which experimentalists go through to make sure that the results of their searches and measurements are useable decades into the future, by people outside of their collaboration. Indeed, lots of information is stored on internal ATLAS or CMS platforms, but this is not useful for, say, a theorist, who wants to figure out if their favourite new model is already excluded or not. And indeed, one day we will all be outside the collaboration!

Preserving measurements is, by and large, a solved problem. Since measurements are typically already corrected for detector effects, preserving them is simply a matter of writing up a runnable code snippet (in the RIVET software package) which explains which events enter the selection. You can think of that as a filter, saying which collisions would have been selected and which ones not. Then, the detector-corrected data (in the jargon we call this “unfolded data”) stored on HEPDATA can be directly compared to a prediction which is passed though the corresponding RIVET routine.

Preserving searches is more problematic, since the results re usually presented at “detector level”: in other words they are not corrected for detector effects. The problem is then that theorists with a new model don’t know how to account for detector effects, and have to make guesses, to try their best to do so. This is often insufficient. Also, the use of complex variables, machine-learning algorithms, and similar tools which sometimes depends on the detailed detector response pose further complications.

My work

My work in phenomenology has focused around exploiting measurements for re-interpretation. This has chiefly been achieved through the CONTUR project: the goal of this is to exploit the RIVET routines mentioned above, inject new physics simulations into them, and see where they would have been visible in the bank of hundreds of LHC measurements made to date. If they would have caused a visible variation in well-measured observables… then you can set constraints on them based on that!

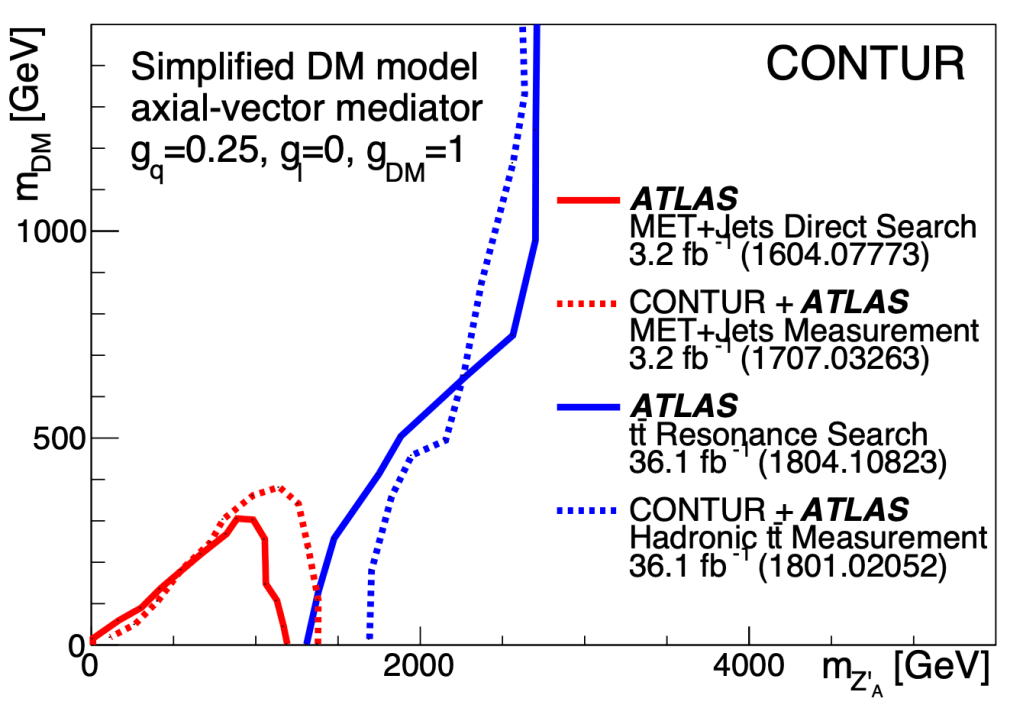

This approach has been shown to be pretty much equivalent to doing a direct search for a new physics model, but very flexible in terms of re-use because you don’t need to worry about detector effects (they have already been corrected for in the measurements we use). An example can be seen below, comparing direct searches for a Simplified Dark Matter model with CONTUR re-interpretations using a similar final state and the same dataset. The dashed and solid lines, which represent the exclusion at 95% confidence level, overlap very nicely!

This work has led me to work also on the RIVET software package, to write the manual for CONTUR, and produce several papers studying the exclusions derived from CONTUR for new physics models such as Heavy Dark Mesons and Vector-like Quarks.

An example: the grey region in the below ATLAS result on Heavy Dark Mesons was obtained from our CONTUR paper, while the ATLAS direct search exclusion is represented by the orange band. You can see there are regions where CONTUR excludes the model when ATLAS does not, and vice versa. A nice complementarity !

This line of research has also helped me to become an established name in the re-interpretation community and advocate for it within ATLAS. I’ve given talks on re-interpretation and international al conferences pan-LHC meetings, ATLAS workshops and collaboration meetings, and authored the ATLAS analysis preservation policy.