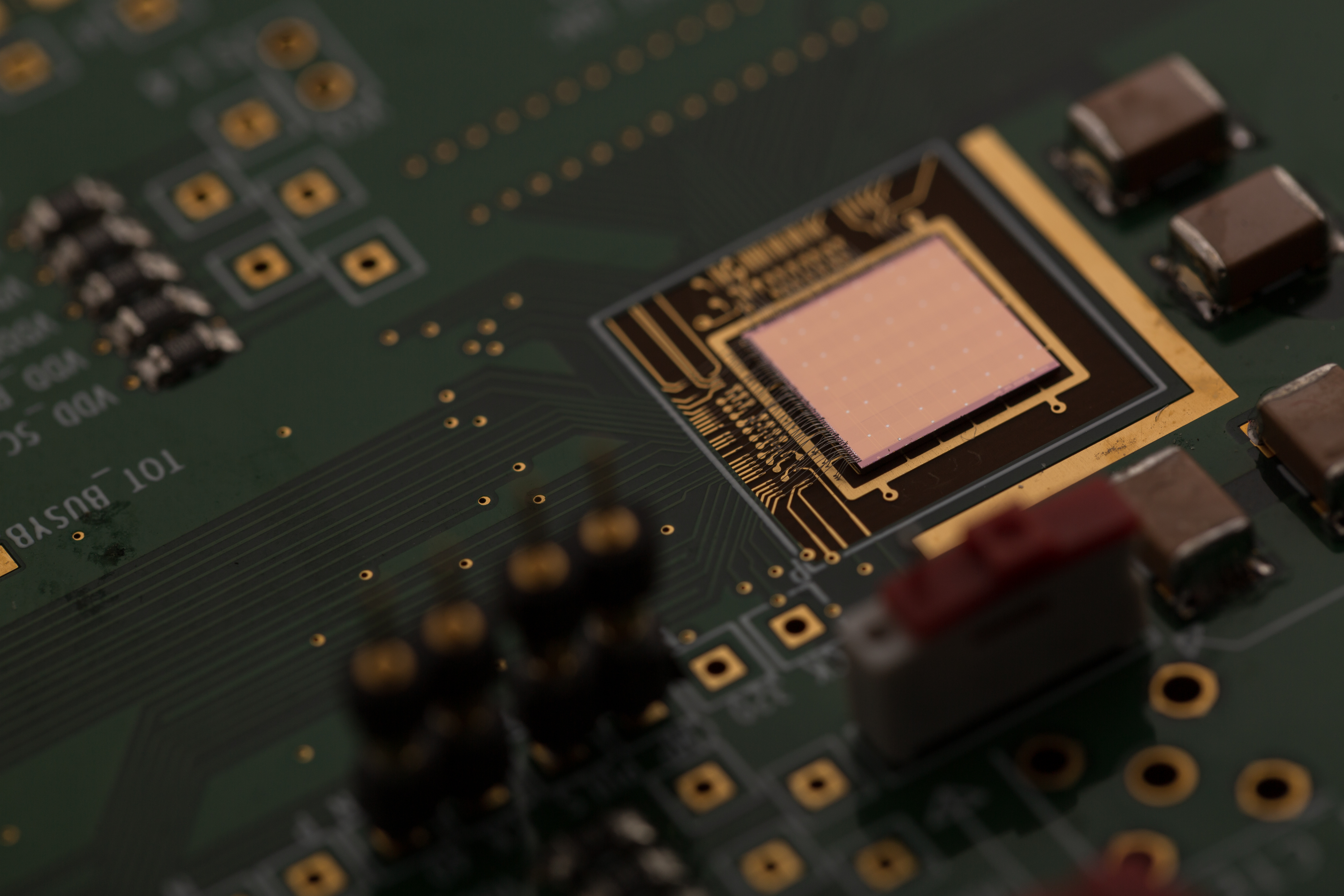

An LGAD sensor array mounted on a readout chip.

Photograph: Jérémy Barande, ATLAS Experiment © 2021 CERN

Designing a new-generation timing detector for the ATLAS upgrade

The ATLAS detector has been thirty years in the making, and in operation since around 2010 in LHC beams. Those beams, which are composed of protons, produce a hefty dose of radiation, which, over time, degrades the detector. And that means we will need to replace some parts of it ahead of the high-luminosity LHC (HL-LHC) runs starting around 2029.

But we won’t just replace like-for-like. The technology ATLAS is built on is now decades old! We can do much better than to keep to the same technology, and indeed, we will need to do better… the HL-LHC will collide particles at an intensity never seen before. In the jargon, this means we will have much more pileup. Translation: we will have a lot more interactions in the detector happening at almost exactly the same time. At the moment (circa 2023), we have around 40 interactions during any one proton bunch crossing, of which only one is every likely to be on interest. The task of locating the interesting vertex, and ignoring the noise from the other vertices, is done by tracing back the tracks of the particles we measure, which should point back to the vertex we want.

At the HL-LHC, we will be upgrading the tracker to have a new an improved spatial resolution, which should help us to ignore the extra pileup vertices and associated activity… except that there will be so much pileup that it won’t always be possible to uniquely match tracks and vertices. Even our improved spatial resolution won’t be good enough… this would significantly deteriorate the physics performance of ATLAS. So what can we do?

Enter the 4th dimention

One possibility is use more information than just the spatial positions of tracks and vertices. Another axis we could use is time! If we have a detector with sufficiently good timing resolution, we can uniquely sort tracks and vertices by grouping together those which are nearby in time. But I hear you cry “Hang on, don’t the LHC collisions happen every 25 nanoseconds? How can you distinguish activity in a window smaller than that?”

Well, the answer is that we need a detector with timing resolution far bellow 25 nanoseconds. Thankfully, we can benefit from 20 years of advances in technology. Indeed, the original ATLAS experiment was being designed and assembled nearly 20 years ago, believe it or not! We now have tools, sensors and capabilities which we could only dream of back then, to help us with the upgrade of the detector. And one such advance is “Low Gain Avalance Diodes”, which we lovingly name LGADs.

Low Gain Avalanche Diodes

LGADs are a type of silicon sensor, which have a special property: their signals rise and fall extremely quickly. In layman’s terms, that means we can distinguish two electrically charged particles even if they passed through the sensor at almost the same time. Indeed, the timing resolution of these devices is approximately 50 picoseconds. That’s 50 billionths of a second! Nearly 1000 times smaller than the 25 nanosecond gap in between LHC collisions. This technology allows us to solve the problem mentioned earlier: we can use this amazing time resolution to uniquely assign vertices and track even in high pileup environments!

The High Granularity Timing Detector

The High Granularity Timing Detector is the name of the array of millions of LGAD sensors that we will arrange in disks on either side of ATLAS, which will allow us to benefit from this resolution. It’s not just a case of putting the sensors together: they need to be cooled to nearly -30C, and they need data acquisition chips which also have picosecond-scale resolution. All this, and the whole assembly needs to fit within the 6cm gap between the new ATLAS tracker which is being built, and the rest of the detectors behind. It should be installed in 2027 or 2028, and be operational for the start of the HL-LHC collisions in 2029! There is a lot fo work to do in that time, and my team and I are contributing to this project in a variety of ways:

- Designing a surface commissioning system, so that we can test if the assembled system works alright before it is lowered into the experimental cavern in 2027.

- Participating in beam tests to ensure that the LGADs and readout chips meet the specifications for the project to work.

- Helping to build a demonstrator for the cooling system to maintain the whole apparatus at -30C.

- Imagining and testing ways to exploit this new detector beyond the pileup-reduction. Some ideas include using the HGTD to reject one of the main backgrounds in searches for long-lived particles (Beam-induced background).