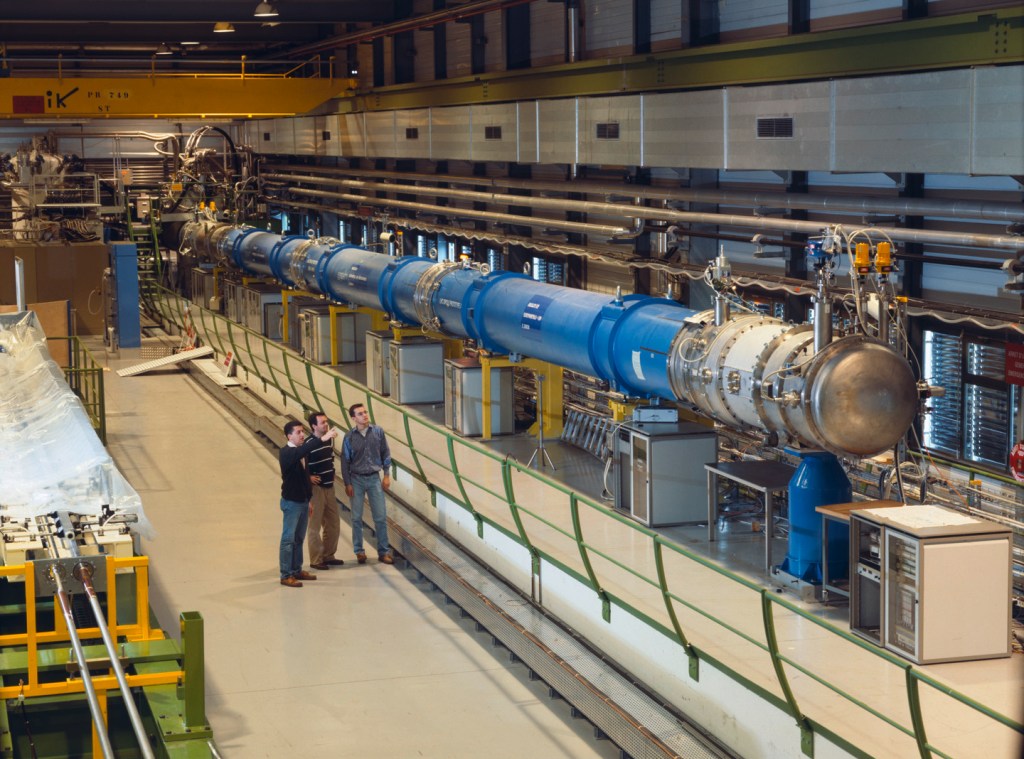

Image: LHC magnet being assembled. If Particle Physics were a railway, CERN would be in charge of laying and maintaining the tracks and signalling. Image © CERN.

This weekend, I’ve been visiting some friends from my university days. While catching up, they asked me a question which I get a lot: are you still working with CERN and ATLAS after moving to Clermont-Ferrand ? It made me realise that it’s probably a bit mysterious to the outside world what the relationship is between CERN, ATLAS, and the universities or laboratories we work for. So I am dedicating this post to explaining how it works!

The first thing to note is that CERN itself is not a university. That might seem an obvious statement, but it has a practical implication: CERN can’t award PhD degrees. Only universities can bestow qualifications like that. Since there are thousands of PhD students working on CERN experiments, they must get their PhDs from somewhere… Indeed, universities from around the globe have research groups which exploit the data from collisions which take place at Large Hadron Collider. The data themselves are collected with vast detectors, which are built and maintained by scientific collaborations. Examples include ATLAS, CMS, LHCb, ALICE, but also a host of smaller non-LHC experiments. So when I say “ATLAS”, it can mean either the detector itself, or the collaboration of university research groups who exploit it.

The collaborations produce scientific results in the form of academic research papers, and PhD students write their theses based on the papers they have worked on as well as any work done to upgrade, maintain or operate the detectors. Post-docs (post-doctoral research assistants), staff scientists, and academic staff (lecturers and researchers) all take part in a similar way, analysing the collected data to produce new physics results.

CERN itself can be seen as an infrastructure provider. They maintain the LHC, and provide a campus where scientists can meet, exchange ideas, and work collaboratively. Indeed, every university which takes part the collaborations has one or several offices at CERN. Many universities also choose to base part of their research staff in Geneva full time. The collaborations exploit the infrastructure and produce papers.

One could use a railway as an analogy. CERN would be in charge of laying the track and maintaining the rails and signalling. The collaborations would be in charge of building and running the trains. The universities provide the staff to maintain and exploit the trains to run a service.

The researchers who form part of the collaborations are typically not employed by CERN, but by the hundreds of participating universities and institutes*. Further, they need not be based on site at CERN, even if they hold organisational responsibilities. For example, I am employed by Université Clermont Auvergne to lecture for about half my time, and work on ATLAS the rest of the time. I go to CERN perhaps once every couple of months to meet colleagues, or give presentations.

Maybe a question remains: who pays for CERN to exist? Who pays for ATLAS (and the other collaborations) to run? CERN is funded by contributions from participating states directly. European countries can be member state (it is a European lab after all), and other countries can be observer states. All of them contribute something to the CERN budget, roughly according their membership status and to their GDP. That helps pay for the running of the LHC and related infrastructure. The collaborations are funded by the participating universities (or by their funding bodies). A fixed contribution is due for each author (post-PhD) of the ATLAS collaboration. That helps fund the operations (data-taking) and upkeep of the detector.

Finally, how is it possible to analyse the data from ATLAS remotely? Well, it may surprise you to learn that particle physicists have always been keen to find ways of sharing data: the World Wide Web was literally invented to share data from the previous generation of experiments back in the 90s. Many participating countries pledge computing resources, and the ATLAS data are replicated in many sites across the world. Data analysis tasks are transmitted to wherever the relevant data samples are stored, and the results sent back. This system is called the “World-wide Computing Grid”, or just affectionally as The Grid. The heavy number-crunching never happens on a local computer anyway, it is delegated to whatever storage and processing facility is best suited. Hence, to analyse LHC data, I only need is a laptop and a ~stable internet connection. I’ve analysed data in all sorts of places: from my desk, from beside a pool, from up a mountain while hiking, on the train, from a chairlift on a ski-slope….

So, in summary: there is no need to be based physically at CERN to participate in analysis of LHC data: in fact, most people aren’t. One does need to be part of one of the experimental collaborations (CMS, ATLAS and similar), which is composed of hundreds of universities and institutes. They are the ones who employ the collaboration members and award degrees to the PhD students. It means that the whole world can take part in this scientific adventure together.

* although, to complicate things, CERN does also have a research group, but without PhD students since they can’t award degrees.