Image: The planned location of the Future Circular Collider at CERN. Credit: CERN.

Sometimes it’s easy to forget that the entire field of particle physics is less than 130 years old. I pick as a starting point the date that we discovered our first fundamental particle: the electron (discovered in 1897 by J. J. Thompson). In the intervening 129 years, we have gone from not knowing anything about fundamental particles, to validating a hypothesis as subtle and incredible as the Higgs mechanism.

It’s been an incredible roller coaster ride for humanity. And it’s all happened in such a short time that nearly a third of that epic journey has happened within my lifetime. When I was born, the top quark was still a hypothetical particle, and W and Z bosons were still recent discoveries (today they feel like impossibly old news!)

The meteoric pace of discovery in the last 130 years has required ever increasing infrastructure and instrumental complexity. We have benefited from the technological exposition in the last century has helped us in our journey. For example, the Z boson was made with a handful of candidate particles in the 80s [1]. Today, forty years later, we produce millions of measurable Z bosons at the LHC. In another few decades, the Future Circular Collider is expected to produce over a trillion Z bosons, so that we can study the properties of its interactions in exquisite detail. This has all been possible due to incredibly fast development of semiconductor, magnet and cooling technology.

The fact that we need more and more complex machines for our work inevitably means that discoveries will now come at a slower pace. Humanity was “lucky” that so many of the fundamental particles were within relatively easy reach, but getting the full picture is will take time. Instrumental leaps will require more and more planning and R&D, and now we are coming to the stage that the plan we are laying out for the future of particle physics is on a longer timescale than a typical human life. That might sound frightening at first, but I am here to an argue that it shows some of the best qualities humanity has to offer.

The LHC will operate for another decade and a half. After that, the field seems to be slowly converging on the Future Circular Collider (FCC) as the next major infrastructure project. It will have a circumference nearly four times that of the LHC’s. As a first phase, it would operate as an electron collider (FCC-ee), for precision measurements of the Z and Higgs boson properties. That would be in the 2040s-2050s. And after that, the plan is to convert it to a hadron collider (FCC-hh) like a giant version of the LHC operating at nearly six times higher energies, in the 2070s. That’s nearly half a century from now.

We have good reasons to think that a treasure trove of discoveries may await us when that collider turns on. But even though I consider myself still “early” in my career, I will be unlikely to see it as an active physicist. As much as I love my job, I will be in my mid-80s by then and probably should not be coming into the lab anymore. With a bit of luck I might still be alive to see some of the wonderful scientific harvest, but if (let’s be honest) the schedule gets delayed by a significant amount, I won’t get to see it.

Despite the fact that many of us will never see its operation, there is a huge amount of effort to plan for that future. I find that truly beautiful, because it exposes that all this planning is not for anyone’s personal gain or glory, but so that our children and grandchildren can understand the universe better than we do. believe it or not, the LHC was first proposed in the 1960s, and many of the original proponents of ATLAS and CMS are no longer with us: in other words, we are not new to generational projects. It shows that the scientific gain of the future collider programme is a gift we are giving to future generations, but also a mark of our trust in our descendants to become custodians of this gift. We are all laying our stone at the edifice, and taking part in the ongoing rollercoaster of scientific discovery, and that unites us across borders and eras. I can’t sum it up better than this quote from one of the fathers of the Standard Model, Abdus Salam:

“Scientific thought and its creation is the common and shared heritage of mankind”

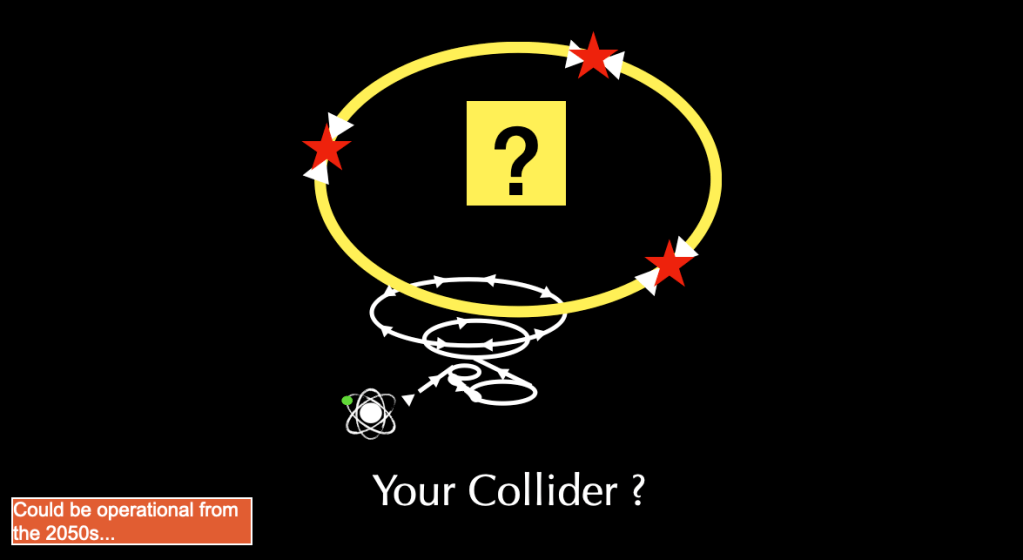

When I do outreach events in schools, I love to use this image from the last page of Particle Physics for Babies to finish off my presentation:

I explain to them that the yellow ring represents a new collider. But that in the 2050s, I will be approaching retirement. It won’t be me exploiting that machine.

I ask them, who do you think will be exploiting it?

You should see the light in their eyes as they realise that it is them I am talking about.

[1] Incidentally, the W and Z discovery papers would obsoletely not have reached the modern statistical thresholds for particle discoveries, but that just shows how far our understand of statistics has progressed in that time too!