Image: Louie preaching to the converted (during a visit of his masters students to ALICE experiment at CERN in December 2025). Credit: Adrien Auriol.

I would like to dedicate this post to the memory of Deepak Kar, who passed away tragically last week after a short illness. We co-organised the CHACAL school together, and I had the pleasure of calling him a friend as well as a collaborator. May we take inspiration from his good humour and ability to challenge received wisdom, and above all, his drive to pursue ideas and work which he found interesting and fun.

As 2025 draws to a close, I wanted to look back and take stock of what we have learned. In recent years, the field of particle physics has felt like it is stuck in the doldrums, because we have not discovered any new fundamental particles since the Higgs. I think we need to change this frame of mind as we look to the future, because after all, every time we publish a paper, we are learning something new about nature. Slowly but surely, we are chipping away at our ignorance. Hence, let me take a few paragraphs to celebrate the things we have learned this year. Here are my top five, which I assembled for a talk I gave at the LHC Beyond-the-SM working group general meeting in November.

Lesson 1: Oooooh, we’re halfway there !

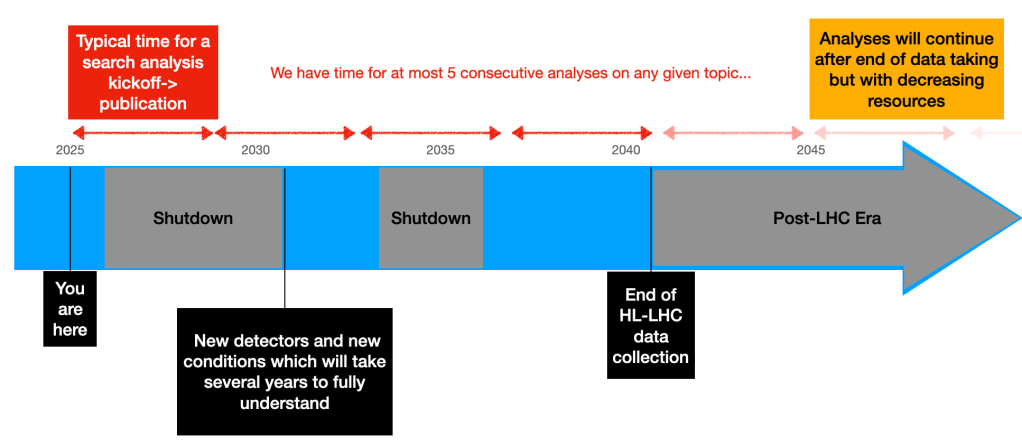

Bon Jovi probably didn’t mean it in the context that I’m about to use it… but his famous lyrics also apply to the LHC. Indeed, we started collecting data around 2010, and the LHC is due to continue operating until about 2040. That’s a 30-year lifespan, and this year, 2025, is the halfway mark. The first important thing to take away is that the LHC will not last forever. We should bear that in mind when planning the rest of the physics programme, because we do not have infinite time or resources. We need to find a way to plan and prioritise, to make sure we reach our objectives by the time we collect the last collision. That requires us to take stock of how far we have come in 15 years, and have an idea of what we want to achieve in the next 15 years. And we should never forget that our #1 objective is to make the discovery of a new particle… or be sure (at 95% confidence level!) that there was no discovery to make. We do this by exploiting the strengths of our people to ensure deep but focused coverage of the best-motivated new physics models, and also broad but shallow coverage for more speculative models and wild ideas. These should be scheduled in time according to potential gains in sensitivity, and with a critical mass of people working on it to converge in a reasonable time. We should make the best use of the extra data and instrumental developments, and design searches for long-term impact to avoid repetition of work.

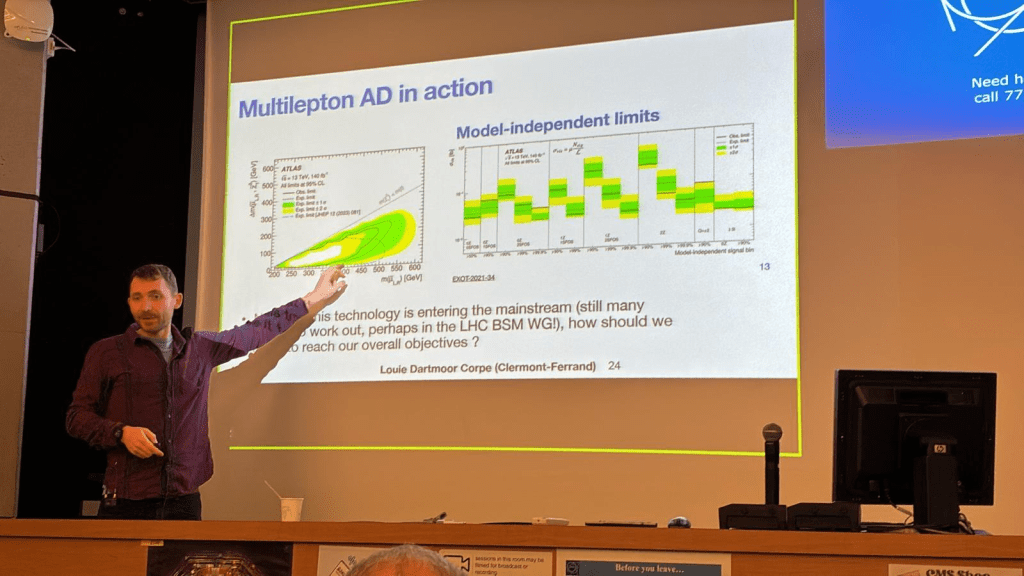

Lesson 2: The machines are coming to steal our jobs

Ok, the section title is clickbait. “The machines” are a long way from being able to do our job, but we should make sure to use them properly to best complement our research. Both ATLAS and CMS have started publishing anomaly-detection (AD) based searches (a kind of machine-learning or “AI” algorithm which finds outliers or overdensities in a population), mostly searching in hadronic final states which are messy and hard to decrypt. But something new this year is that we published the first AD search in leptonic final states.

Image: Louie highlighting a new ATLAS anomaly detection search in leptonic final states at the LHC Beyond-the-SM working group general meeting in November 2025. Credit: Flavia Dias.

The question which both the CMS and ATLAS collaborations are facing now is: now that AD technology is coming into the mainstream, how do we best use it to reach our research objectives (see Lesson 1)? In my view, it’s a beautiful serendipity that this type of algorithm is coming online just as we realise that we need to cover a lot of ground in model space in a short time. Indeed, if one needs broad but shallow coverage of entire classes of models, that’s exactly the kind of problem that AD can help with. But a new type of analysis means we can’t naively rely on our established validation methods and procedures: and that’s why both collaborations are working on guidelines to help grow this aspect of our research programmes safely and in a controlled way. So watch this space for the development of this exciting side of the physics programme at the LHC.

Lesson 3: I’m silently judging you for not recycling.

… and I’m not talking about the mountain of Christmas wrapping paper in your black bin. I’m talking about physics analyses. In Lesson 1, I talked about making sure analyses have long-term impact, and are designed such that we don’t needlessly repeat work. That’s because if we have finite resources, we cannot afford to have to re-do analyses if we can avoid it. The way to do that is to ensure that we go the extra mile for every single search, to ensure all the details are properly preserved. That way, a theorist can come along in 30 years’ time with a new model, and can work out what a given search has to say about that model without having to re-run any ATLAS or CMS code. Remember: in about 20 years’ time, the collaborations will probably have wound down. We cannot afford to say “we’ll do the analysis preservation properly next time” because for some searches, the extra data will not give us more sensitivity (for example in cases where systematic uncertainties dominate). In that case, the papers we are publishing NOW may be the last word we have from the LHC on a given topic. Why have I been thinking about this in 2025? Well, because one of the “flagship” dark matter searches (the “Monojet” search) which we published a few years ago was put out without all the auxiliary information which theorists needed to re-run the statistical analysis with a new model. As Exotics convener, it’s my inbox that all the theorists’ after-the-fact requests land in. From that experience, I can say, that theorists really, really, want as much information as they can get their hands on. For the Monojet search, we have published the needed information after the fact, but for the next generation of papers we should get it right first time.

Lesson 4: We have excesses to follow up

As I mentioned earlier, it is often bemoaned that we have made no new discoveries in the last decade. Normally, the first sign of a discovery comes when one sees an excess of events in a search. Well, despite the doom and gloom, it turns out there are exciting excesses around. This became obvious to me as part of an LHC BSM WG effort to document and collate a list of all current excesses. It was a bit of a tedious exercise going through all the ATLAS Exotics papers from Run 2 to figure out which ones had meaningful excesses. But it was worthwhile, because now there is a very nifty page listing them all, across all the search groups of ATLAS and CMS.

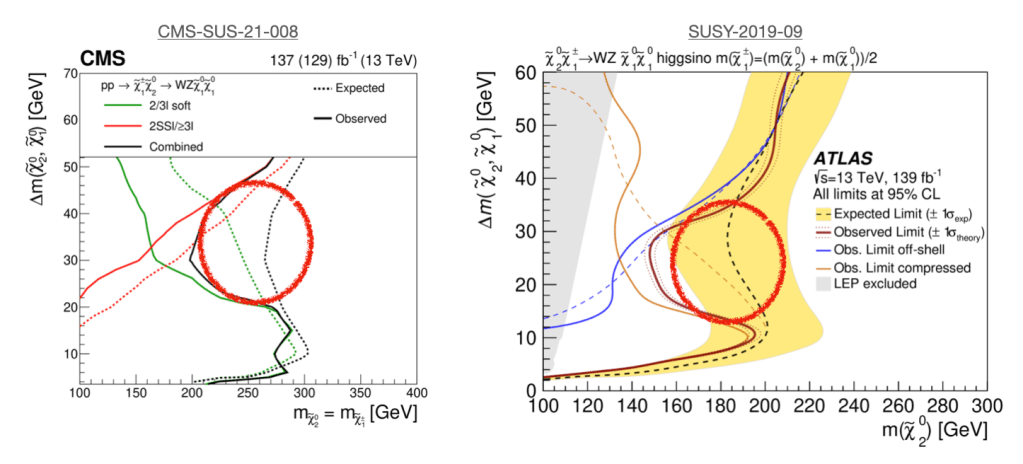

It turns out there are some exciting and intriguing excesses to follow up. A cool example is compressed SUSY searches in low-energy lepton final states, where both ATLAS and CMS see similar anomalies. We should invest huge resources to follow this sort of thing up. Because even though the received wisdom is that SUSY has been largely ruled out, it remains one of the best-motivated extensions to the SM which we can think of. And it is still entirely possible that a surprise discovery could happen… speaking of which…

Lesson 5: Surprises can still happen, and they did in 2025 !

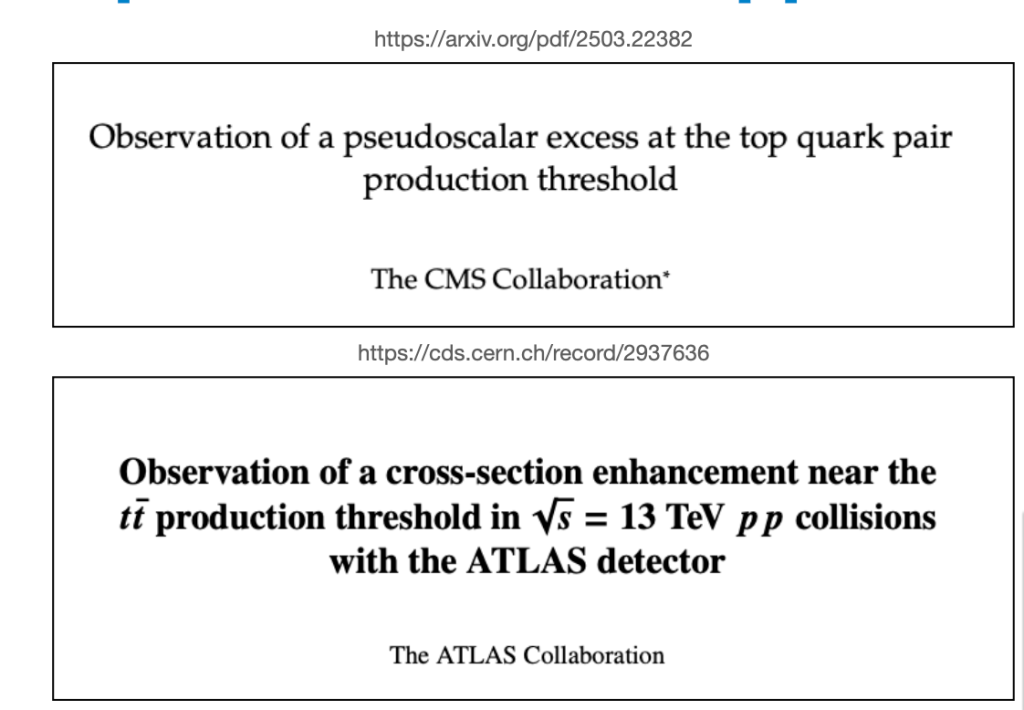

I say surprises can still happen, because in 2025 ATLAS and CMS did discover a new particle… or at least a semi-stable bound state of top-antitop quarks called “toponium”. Although this particle was not a fundamental one, it is a major step forward in our understanding of the strong force. There are so many interesting things to say about toponium, but I will limit myself to linking you to the ATLAS physics briefing about it. What interests me about toponium for this article is the sociological aspect, because this was a discovery which came almost entirely by surprise. There was theoretical knowledge that such a bound state might be possible, and even basic calculations for the rate at which it should be produced. A back-of-the-envelope calculation would have shown that it was discoverable. And we could even see hints of it in a whole range of searches and measurements in top-related final state analyses. Once it was discovered, it made a huge splash in the community, making waves and news articles round the globe. And yet, no one in the experimental collaborations was looking for it. No one was writing grant applications centered around toponium. Few theorists were agitating for us to make this a priority. ATLAS even published a search with over-conservative uncertainties which indirectly seemed to rule out such a resonance. And yet, in the space of a few months, we went from that state of affairs to a five-sigma discovery by both collaborations, to much fanfare.

I was involved in the ATLAS internal discussions because for a short time, no one could be certain if it was really “toponium” or some new-physics bound state. In the end, it was the former, but in my mind the whole affair was a dress rehearsal for a real discovery of a new exotic particle. It proves to me that surprises can still happen, and they can sometimes be hiding in plain sight. It’s easy to think that a pernicious source of mis-modelling in our simulation is down to our generator programmes. But what if, as for toponium, we were subconsciously explaining away a genuine excess and burying it under a mountain of systematic uncertainties, because we had convinced ourselves “there are no new particles to discover, so what I am seeing must just be a problem” ? It’s both worrying – because we could be missing a discovery in other final state – and exciting, because there could be surprises hidden not so deep in our data.

Looking to the future

So with that, my New Year’s resolution is that we should sweep away our cobwebs and be more open to the idea of surprise discoveries in 2026 and all the way until 2040. Let’s follow up existing excesses, and take them seriously instead of just assuming we will find no new particles. Let’s make searches which will last the test of time, and make the best use of emerging technologies to reach our objectives. We are entering the “half-time” of the LHC. As any football or rugby fan knows, victories sometimes come not only from the performance in the second half of the game, but even in the dying minutes or seconds of the match. Regardless, the first 15 years of exploitation of the LHC have brought us so much in terms of our understanding of nature, let’s make even more of the second half.

Wishing you all a happy and restful end to 2025, and see you in January to continue the adventure !