I recently had the pleasure to give an overview talk at the 15th Long-Lived Particle workshop, held in Spain in Valencia (although unfortunately I was not able to be there physically myself). It was a great pleasure because until recently, I was a member of the organising committee for that workshop, which has grown from humble beginnings to become practically a full-fledged conference, with over 100 physical attendees from the Theory community as well as experimentalists from CMS and ATLAS, and non-LHC experiments. But despite my long-standing involvement… I had never given a talk at this forum!

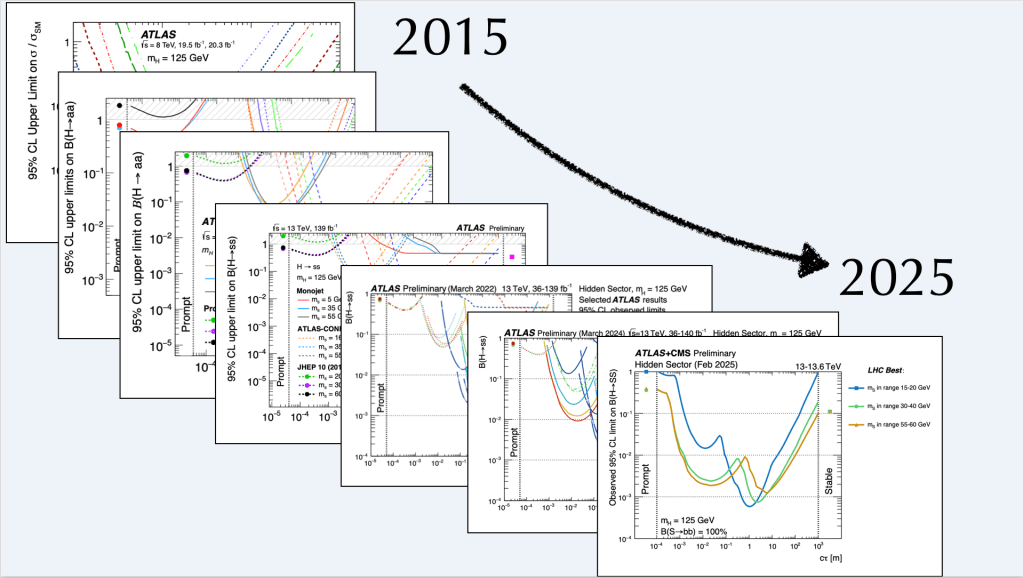

Instead of giving a laundry-list of recent results (each of the 8 new ATLAS results had their own, dedicated presentation), I decided to focus on the big picture. One of the points I wanted to highlight was on how far we’ve come in the last decade, when folks started to realise that exotic long-lived new particles could be in a blind spot. So I did some archaeology and made a timeline of how summary plots (which show the results of different searches on the same plot to give an at-a-glance summary of the experimental status on a given topic) have progressed in the last 10 years.

It was a fun exercise, and it really illustrated how far we have come as an experimental community. The header image of this post shows the 7 versions of the summary plots which saw the light of day in the 10 years. And below you can see the first compared to the most recent, with the areas roughly excluded by the first shown as a blue box on the most recent plot. It shows we’ve gained orders of magnitude in sensitivity in all directions. A phenomenal achievement !

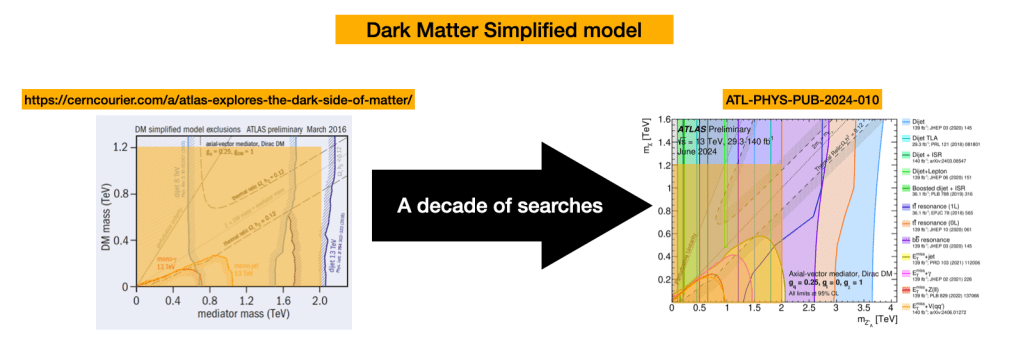

After the talk, I had a bit of fun and did the same for the standard Dark Matter summaries, comparing a plot from 2016 with one from last year.

For this flavour of dark matter, we’ve nearly doubled out reach in the mass of the mediator particle (which would be our link between the Standard Model and dark matter particles) and ruled out basically every part of the parameter space available at the LHC.

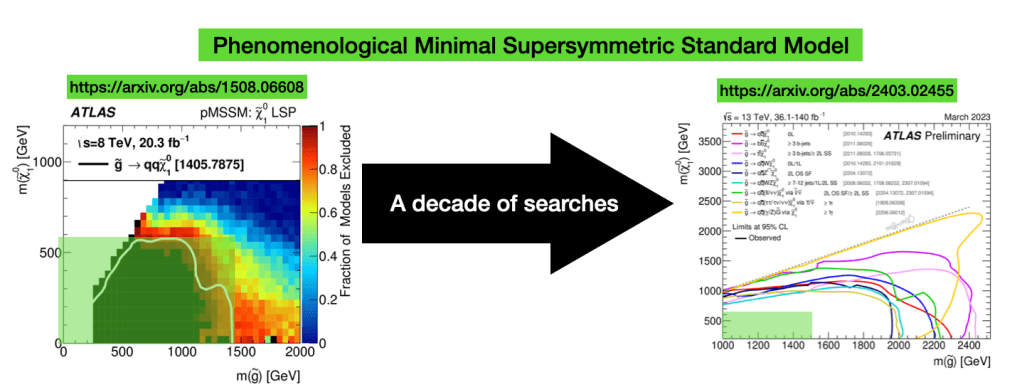

Finally, I did the same with a common supersymmetry model, where once again the constraints have more than doubled in reach in all directions.

Sometimes, it feels that after the adrenaline rush of the Higgs discovery, particle physics has been in the doldrums: no new exotic particles or interactions have been discovered in the 13 years of LHC operation. We often feel this as a sort of failure.

But these plots are here to remind us that we should not take the fact that we’ve not found any new physics yet as a personal affront. In fact, as we can see from the comparisons I posted above, our efforts at the LHC have already revolutionised human understanding of what the most likely underlying building blocks of nature are. Let me explain.

If you go back to the early 2000’s, you’d have been hard-pressed to find a theorist who did not think that supersymmetry was overwhelmingly likely to be discovered shortly after the LHC turned on. “SUSY is just around the corner” was such a common refrain that it became almost comedic. And if not SUSY, then Dark Matter, or something else simple and elegant. But today, the most obvious new particle models have been pushed back to remote (and perhaps implausible) corners of parameter space: in other words, although it may still be possible that SUSY or DM or other models exist at the electroweak scale, it cannot be the most theoretically elegant versions of it. Nature is more complicated than we expected. And we would not know that without the decade of searches which has led to the plots I showed above.

So, no need to be disheartened: every time we unblind an analysis, we learn something new about nature (whether we find a new particle or not). Our job as experimentalists is to measure things we have never measured before, and search for things which we have never seen. We must keep at it, whether SUSY is around the corner or not: we are learning more and more about the universe either way.