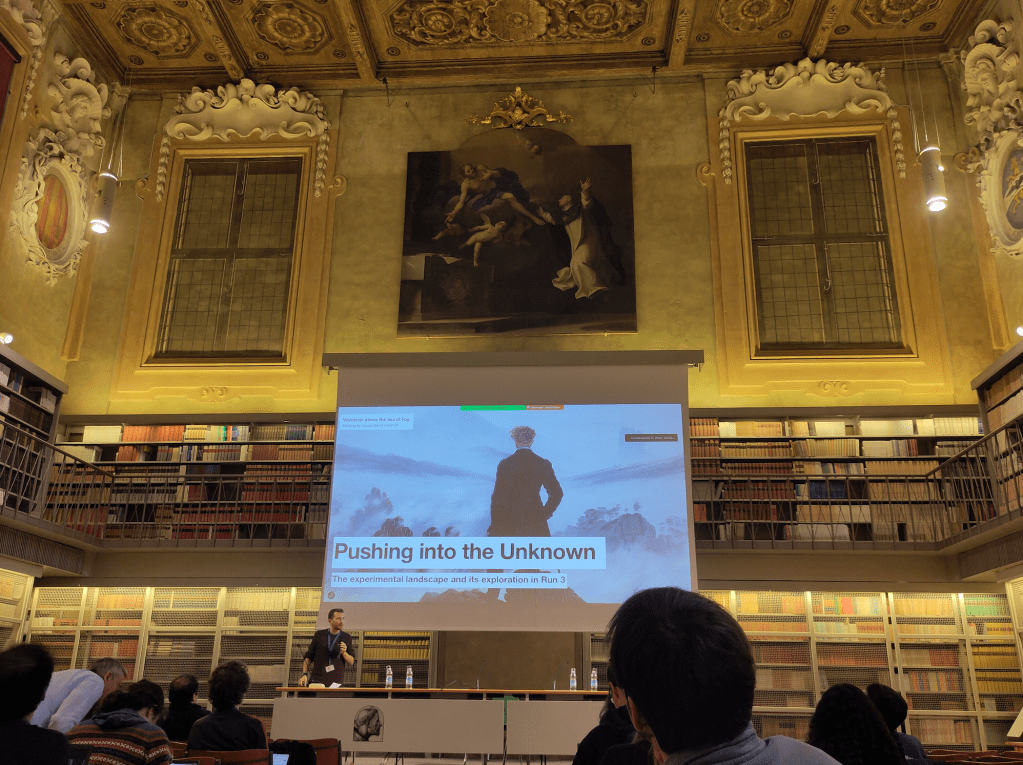

Image: me speaking at the opening session of the ATLAS Exotics Workshop in the San Domenico center in Bologna, October 2024. Photo credit: Bruna Pascual.

At the end of October, I attended the ATLAS Exotics “workshop” in the beautiful city of Bologna in Italy. The word “workshop” may lead you to imagine me in a wood-working studio. But I can assure you that a “workshop”, in particle physics lingo, involves little or no manual labour: it’s a term we use for a (usually annual) gathering of a community to work out priorities, review progress and above all, to be together in person and exchange ideas (and a few beers). I had the pleasure of being one of the co-organisers of this meeting, which gathered together our community of particle physicists searching for signs of new particles in the LHC collision data collected by ATLAS.

Our workshop was held in the beautiful San Domenico centre, which is actually part of the university of Bologna’s faculty of Theology. You can see from the picture above that it provided an enrapturing setting for new ideas and discussions. It was also fun because there were occasionally monks in cassocks walking down the corridors. I’m told (although I have not verified this) that the building we were in was the headquarters of the Italian inquisition in the Middle Ages. I don’t think that the ideas which we were discussing would have passed muster back in those days. The university of Bologna is the oldest continuously running university in the world, having started operations in 1088 (at least 8 years before Oxford!), and today hosts a thriving physics department including colleagues working with us on cutting-edge physics with ATLAS. All this to say that the contrast between old and new was salient at this workshop, as we discussed how to take what we had learned since the Higgs boson discovery to best organise our searches for new particles in the coming decade.

As the incoming Exotics convener, and hence one of the leaders of this community, I was able to open the workshop with a review of the experimental landscape. It was also my chance to set out my stall and present what I deemed to be the biggest priorities facing us. Of course, the details of the content and the discussion are internal ATLAS information, but the broad outline is as follows.

In the past half-century of particle physics, we’ve always known what to look for next. First the W, and Z, then the gluons, and the top, and finally the Higgs boson. All these particles formed part of an evolving but coherent theoretical structure which was a guiding light for experimentalists. But 12 years after the Higgs discovery, we know that there are more particles and forces to discover (see Dark Matter) but we have no preferred theoretical model to guide us. Hence, we are, for the first time, without our torch in the dark. On the other hand, we have the largest scientific dataset ever collected at our disposal. So we need a new approach, which is data-driven instead of theory-driven. And this is a new situation we are adapting to. A paradigm shift.

Thankfully, we have new tools at our disposal. The machine learning revolution is one example, and there are plenty of technical developments which we can make use of. But we can’t just turn the handle anymore. We need to give ourselves space to try new ideas and make breakthroughs instead of aim for incremental improvements.

This really implies a change in mindset, on a lot of levels, from our approach to reporting excesses in data, to allowing ourselves to explore regions not currently well motivated from the theory side. It might involve us trying to go beyond the standard “scientific paper” format, which is limited to a few dozen plots per paper, to something much more vast. But perhaps most of all, we need to make sure we are having fun while doing it. Because you can’t come up with creative, groundbreaking ideas unless you are having fun.

Over the course of the workshop, we had invited talks and panel discussions from theorists who in fact hammered home some of these points. They need experimental input to prompt ideas. We learned that even excesses caused by statistical fluctuations, which eventually go away when you look at more data, can lead to important theoretical developments. So when it comes to pushing into the unknown areas of science, we are no longer simply being driven by the theorists: we are in the driving seat.

One thought on “Pushing into the Unknown”